ISR and the Contemporary Mission Space

The Character of War has Changed

It is no surprise to state that the character of war evolves over time, whilst the nature of war remains relatively stable. War has an enduring nature that demonstrates four continuities: a political dimension, a human dimension, the existence of uncertainty and that it is a contest of wills. Clausewitz, author of the most comprehensive theory of war, provided a description of war's enduring nature in the opening chapter of On War. He observed that all wars involve passion, often lying with the hostile feelings of the people, otherwise states would avoid war altogether by simply comparing their relative strengths in "a kind of war by algebra." He emphasized wars' uncertainty, stating that war often "[resembles] a game of cards." Finally, war is always a matter of policy, as "The political object…will thus determine both the military objective…and the amount of effort it requires," which is a rational process of directing hostile intent normally left to government.

While these continuities are present in all wars, every war exists within social, political, and historical contexts, giving each war much of its unique character (e.g. levels of intensity, objectives, interactions with the enemy, etc.). Therefore "War is more than a mere chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case.” War is fought with the means available at the time to defeat the enemy. S. Kalyanaraman comments that the nature of war (war in general) is violence.

The character of a war or a category of wars is determined by how that violence is applied by the parties to the conflict in question. Wars are fought to subdue an enemy. Clausewitz argues fiercely that the purpose of war is political. “The political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose.” War is a “dual”, thus “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.” It is this last sentence in which lies the hidden gem of warfare. In essence everything that is conducted on the battlefield is for a political objective which is to win the political argument: war is intended to change the will or perceptions of the opponent to a point where they no longer pose a threat.

During the Cold War the battle was between the competing ideologies of Communism and Liberal Democracy. As historian Yuval Noah Harari explains in his book “21 Lessons for the 21st Century”, liberalism has been one of the most dominant ideas in the modern history of humanity. In competition with totalitarian ideas as fascism and communism liberal ideas ended up victorious, something that led to the public intellectuals as Francis Fukuyama proclaiming the “end of history”. As the Cold War ended, a story based on democratic politics, human rights and free-market capitalism seemed destined to conquer the entire world. However, it didn’t and in the void left by the Soviet Union came other contesting narratives, the predominant in the 21st century being extremism.

During the Cold War, Intelligence mechanisms were created to monitor relatively static or slow targets such as ballistic missiles, aircraft, and ships. The US developed sophisticated systems such as the U2, SR-71, satellites, and latterly the F-117 to counter adversary defence systems and be able to collect data with relative impunity. These capabilities were systematically employed against the undynamic targets to ensure that any development made by the Soviets was identified and countered. The best example of this is probably the Cuban missile crisis. Intelligence gathering was routine and predictable against static, predictable targets and the West developed techniques that became habits… and habits are hard to break. New Paragraph

Although there were notable deviations from the static environment of the Cold War such as Burma and (for the UK) Northern Ireland, often in the more dynamic counter terrorism, and counter insurgency operations, intelligence was left to specialist, often national organisations that would operate in isolation and support the specialist Units involve in the conflict. The regular military rarely became involved in this activity. That is until 2001. When the Twin Towers were attacked on the 11th of September, the world changed.

Within 3 weeks the first regular military forces set foot in Afghanistan and stared to patrol the airspace looking for OBL and his cohort. The mechanism to conduct tactical Intelligence was born from the Cold War and as the West entered the highly dynamic Afghan arena, they were ill prepared for the speed and chaotic nature of the mission space. However, in the first year of the campaign all seemed to be going well: the major cities had been secured and stabilised and the Taliban and AQ were withdrawing to the mountains. The West learnt a valuable lesson in this period: when the enemy is massed, ISR is simple; when the enemy is dispersed, ISR is difficult.

During 2001 the Taliban and al-Qaeda were weakened in strength thanks to the OEF campaign. Many of them fled the country, but in January 2002, intelligence reporting was hinting at a potential comeback. Intelligence assessments indicated that a resurgent force was massing in the Paktia province, specifically the Shahikot Valley. The valley sits nestled between the steep mountains and is only five miles long and two and a half miles wide. That topographical nomenclature makes Shahikot a piece of key terrain that is easy to defend, and a potential death trap for an invading force. Following collaborative intelligence assessments, the task force was created, and planning started in earnest. Initial assessments suggested an enemy force numbering 100-200 personnel, the US led task force numbered 2000. Early reporting was contradictory.

The airborne mission commander on duty on day one of the operation received a radio call from one of the US observation posts indicating a far superior enemy force, numbering up to 1000 fighters, embedded AAA sites, bunkers and a comprehensive network of tunnels and protected areas. How did the coalition miss this obvious and significant change. The answer lies in the way tactical ISR was conducted in 2001. The initial assessments of the Shahikot Valley were conducted by specialist Units, however, the updates to these assessments were the responsibility of the regular forces. The latter was not geared for such an endeavour: the tasking chain did not function, commanders did not understand the value of ISR, tactical battle managers were not trained in ISR (being solely focused on Close Air Support). In short, ISR was not recognised as a function of air power. Therefore, when the manned observation posts reported significant changes in threat, there was no mechanism to tactically retask an ISR asset to support. The Task Force responsible for Operation Anaconda were effectively on their own.

Procedures created for Cold War targets sets did not match the dynamic and chaotic nature of Afghanistan. Despite these problems, Operation Anaconda, was described by General Franks as an ‘absolute and unqualified success,’ but one in which the original U.S. military battle plan ‘didn’t survive the first contact with the enemy.’” The fall out of OA reached far and, in the USAF, it started a sole search to prevent this paralysis from occurring again. The work for the ISR Theatre CONOP had begun.

Over the next 5 years various techniques were tested to improve the efficiency of ISR. Everything from ‘spreading the peanut butter’ to the ‘clock dial’ were used. Col Jason Brown (USAF Retired) describes this issue in his paper the Strategy for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance. AFRI Paper 2014-1. In this paper, Brown discusses the employment of the U2 aircraft for counter IED operations. Improvised explosive devices (IED) began taking their toll on coalition forces, causing the US military to spend billions of dollars and dedicate countless resources toward defeating these threats. This included tasking reconnaissance aircraft to find IEDs prior to detonation. Intelligence collection managers routinely tasked the U-2 to conduct change detection, a technique using two images taken at different times to determine changes on the ground. In theory, if an insurgent planted an IED in the time between the two images, an analyst could detect a change on the second image and report the possibility of an IED. Because the collection managers treated all counter-IED requirements equally, the “peanut butter spread” U-2 coverage throughout the theatre.

As a result, the U-2 could not capture the second image required for change detection until four to five days after the first, while insurgents detonated IEDs within hours of planting them. Also, analysts within tactical units had to submit most collection requests no later than 72 hours in advance of the U-2 mission, long before units planned and executed missions involving ground movement. Finally, collection managers discouraged U-2 operators and analysts from interacting directly with ground units for fear the units would circumvent their rigid collection request process. Consequently, U-2 operations did not integrate with the tactical ground operations they were meant to support. The result was little to no evidence that the U-2 change-detection technique found any IEDs.

Despite this lack of evidence, collection managers, concerned more about the percentage of satisfied requirements than flaws in ISR strategy, continued to task the U-2 to hunt for IEDs via change detection for nearly five years. Away from the front line at Nellis Air Force Base the Joint tactic Squadron, the Weapons Instructor School and RED FLAG were all working hard to solve the problem. Weapons and Tactics (WEPTAC) conferences focused on ISR became the norm. In 2007 the first draft was issued shortly after the 2008 ISR Theatre CONOP was released. The document provided, for the first time, a clear methodology for the employment, integration, and synchronisation of ISR.

The identification of a problem and subsequent solution took 7 years and the document saw coalition activities through Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. Along the way there was affirmation that ISR remained critical to operations no more so than in Libya were ISR was deemed as mission critical. During one short period of operations, twenty-two missions were cancelled with 90% of those owing to a lack of SA as to the relative locations of pro and anti-regime forces providing a clear indication (and cost) of the lack of ISR. From the lessons learnt from the UK forces in Libya it was clear that the value of ISR was again proven beyond all reasonable doubt. However, issues still existed. Aircraft and the systems alone could only realise their full potential when complemented by experts who possessed a sound grasp of the capabilities and limitations of ISR.

As in 2001, in 2014 and the invasion of Crimea, the world changed. The mission space moved from the physical to the information domain. And just like in 2001, the West was left with ISR procedures developed in one mission space and forced to fit something new. Information and the information domain had finally been weaponised which demanded ISR to create understanding in the information domain… something that had not been achieved by a regular armed force. Without having time to catch the collective breath, in 2016 two other information campaigns provided more food for thought. The disputed American general election and the UK referendum to leave the European Union.

The Centrality of Influence

“Their goal is to win without going to war: to achieve their objectives by breaking our willpower, using attacks below the threshold that would prompt a war-fighting response. These attacks on our way of life from authoritarian rivals and extremist ideologies are remarkably difficult to defeat without undermining the very freedoms we want to protect. We are exposed through our openness.”

General Sir Nick Carter

In his speech introducing the UK’s Integrated Operations Concept, the then CDS, general Sir Nick Carter described the world in which conflict will occur. The mission space he described was very different from that of the Cold War and distinct from COIN. He described a mission space that was not geographically bounded, one that included actors that defied categorisation and a mission space that was bound together by the ability of non-combatant to influence conflict. What is very clear, is that influence has become central to contemporary warfare. David Patrikarakos wrote, in his book, War in 140 Characters, “What I was seeing went beyond this definition [of hybrid warfare]-this seemed like an altogether new type of warfare. At its centre one thing shone out: the extraordinary ability of social media to endow ordinary citizens, often non-combatants, with the power to change the course of both the physical battlefield and the discourse around it.”

It is within this reality that ISR finds itself, and it finds itself lacking, due mainly to the fact the ISR process clings to decades old methodology built against targets that no longer exist. The mission space has moved and like the magician removing a tablecloth from a fully laden table, ISR if left behind rattling slightly as the world moves by.

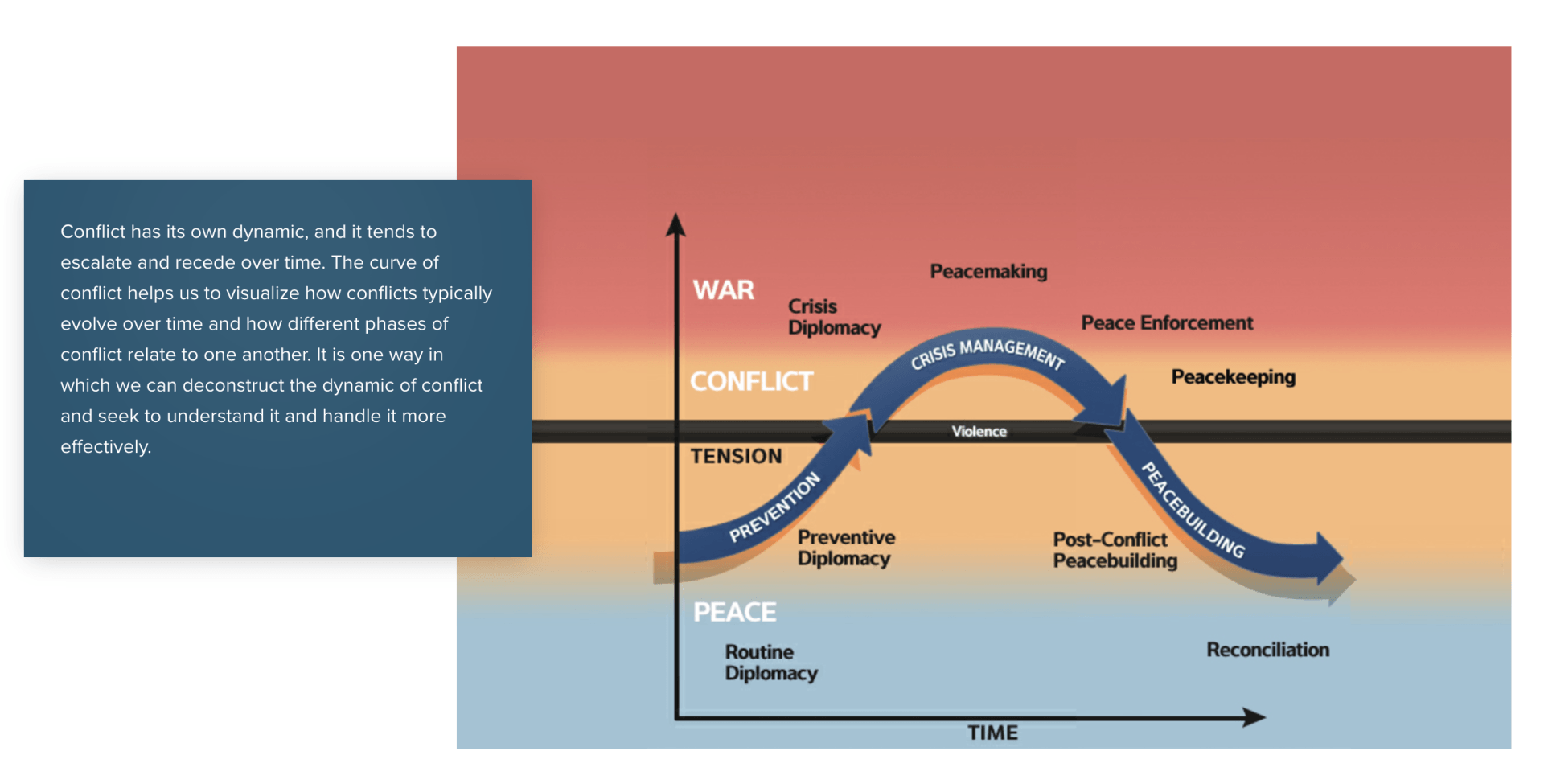

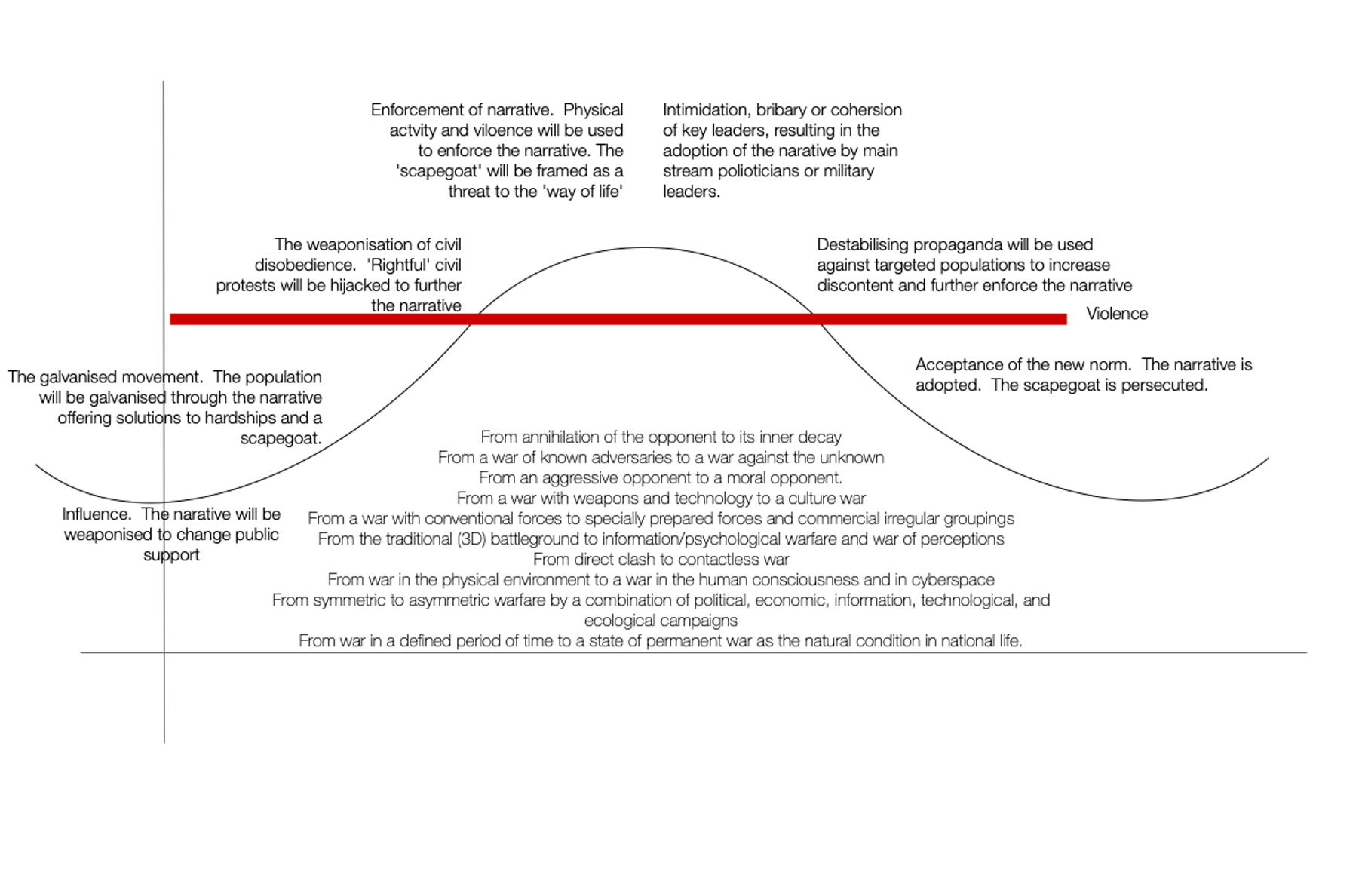

Sub-threshold or Grey Zone actions are not new. If you take Lund’s Model of constant competition activity below the line (sub-threshold) is an indicator that tension may be rising, and a situation may be moving towards conflict. Lund clearly states that sub-threshold activity is dominated by diplomacy, back-channelling, and politics. If we put the graph in a contemporary setting, we see something different.

In the contemporary setting, sub-threshold activity is now outside of the control of governments and firmly in the hands of influencers and social media platforms. Influencers will change perceptions and opinions over extended periods of time in insidiously small steps. It is the responsibility of the intelligence community including the ISR fraternity to create understanding in this area to ensure that a nation can identify trigger that will suggest conflict.

Influence is not limited to social media platforms. Traditional militaries can be used to influence. Take recent Russian and Chinese military exercises. I am sure that their military goal was to train and practice joint operations, but I would suggest that their primary aim was to influence a target audience. This audience will be non-combatant: the Russian population proving that Putin and Russia have strong allies; the American public; the American government; the European population and the EU. The Russian manoeuvre occurs in the physical domain, but the intended effect is influencing the cognitive domain.